Review Veteran raconteur hits right notes in Charly’s Piano

Review Veteran raconteur hits right notes in Charly’s Piano

WhatsOn Dec 5 2017 05:26 PM by Gary Smith, Hamilton Spectator

Charly Chiarelli recalls the world of 1970s Toronto in “Charly’s Piano.”

Want to go back to the early ’70s? To a time when Ian and Sylvia, Bo Diddley and Ronnie Hawkins sang at the Concord and other hallowed Toronto halls?

Coffee houses and bars were still the domain of beatniks and hippies back then. Toronto was less sophisticated than it thinks it is today. Possibilities were endless.

In 1972, Charly Chiarelli, born in Racalmuto, Sicily, but raised in Hamilton’s gritty North End, found himself wandering the streets of what was once called Hogtown.

He found an attic abode next to a Primal Scream Clinic near Kensington Market. He found a job, too, at Toronto’s prestigious Clarke Institute of Psychiatry. Called an observer, he was paid to watch patients. Memories of many of these institutionalized folk permeate his new play “Charly’s Piano.”

Written by Chiarelli and Artword director Ron Weihs, the play is sometimes a rambling discourse through Charly’s world. It’s punctuated by haunting riffs on a harmonica pulled from Charly’s jacket pocket. That music is nicely supported by Weihs’ expert noodling on an old guitar.

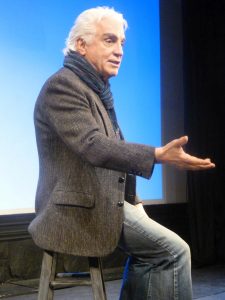

Something of a local icon, Chiarelli bounds onto the tiny Artbar stage in jeans and a tweed jacket, an attractive scarf knotted round his neck. He has a mile-wide smile with tufts of white hair poking out from behind his head.

The voice is raspy. No matter, Chiarelli acts his songs as much as sings them.

He falls into character, melting years away, easily becoming the boy he was back then.

His story is filled with detailed remembrances of patients from those Clarke days.

There’s Beatrice, the Cat Lady. Her Siamese cats taught her to read minds.

And there’s poor Adam, a casualty of the system who jumped in front of a subway train when out on a day pass.

There’s also psychotic Philip, an expert on math, physics and chemistry.

Charly’s treasure-trove of remembrance leaps into high gear when he recounts how he decided to put on a concert in the Grand Rounds room of the Clarke and needed to buy a piano for the patients to enjoy. We hear how the doctors, staff and residents, after initial reluctance, come forward to make things happen.

One of the most affecting parts of Charly’s story is his recollection of going to some out-of-this-world mansion with a patient called The Duchess to buy the piano on a stormy winter night.

Judith Sandiford’s evocative projections fill the wall of the tiny stage with recollections of a Toronto long gone.

These images amplify the words of “Charly’s Piano” beautifully, transporting us (if we are of a certain age) to a time we remember fondly.

Just as Charly’s songs hint at loss, these photos suggest the warmth of recognition, reminding us that change doesn’t erase the past from the present, but rather gives it context. This is because Sandiford’s projections, like Chiarelli and Weihs’ words, create a time tunnel to something gone by.

There are cavils:

At two hours, including intermission, the show is just too long. It would sit better in a one-act format, running 75 to 90 minutes. No intermission.

There are almost too many memories of patients here, too many anecdotes and the lead-up to the essential piano part of the story takes too long.

The show, seen at a dress rehearsal, needs tightening, as well as editing.

In the end, it is a warm-hearted, tender story acted by a friendly raconteur, a storyteller who delivers memories with sweet recollection of time passed by, but never forgotten.

Gary Smith has written on theatre and dance for The Hamilton Spectator for more than 35 years.