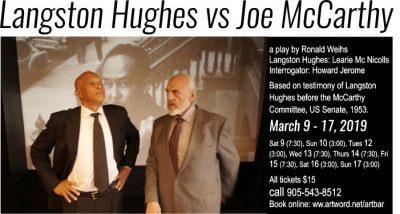

March 9 to 17, 2019. Artword Theatre is bringing back its timely and sensitive piece of documentary theatre, Langston Hughes vs. Joe McCarthy, written and directed by Ronald Weihs and produced by Judith Sandiford. Dancer-choreographer-actor Learie Mc Nicolls plays the role of Langston Hughes and character actor Howard Jerome plays The Interrogator.

March 9 to 17, 2019. Artword Theatre is bringing back its timely and sensitive piece of documentary theatre, Langston Hughes vs. Joe McCarthy, written and directed by Ronald Weihs and produced by Judith Sandiford. Dancer-choreographer-actor Learie Mc Nicolls plays the role of Langston Hughes and character actor Howard Jerome plays The Interrogator.

Permission for the use of the poems has been granted by Harold Ober Associates Incorporated, for the Langston Hughes Literary Estate.

Is poetry subversive? U.S. Senator Joe McCarthy thought so.

On March 24, 1953, Langston Hughes, renowned poet of the Harlem Renaissance, was summoned before the Senate Committee on Investigations. Did his poems contain communist ideas? In reply, Langston Hughes tells about his personal encounters with racism in America. The script is based on the actual transcript of his testimony, interwoven with the controversial poems, and incorporating dance, music and powerful images of the era.

Only 8 performances! Runs about 60 mins. All tickets $15.

*Sat March 9 at 7:30 pm, OPENING Special, stay for the Beg To Differ concert at 9 pm (no extra charge) .

*Tuesday to Friday, March 12-15 at 7:30 pm,

*Three matinees at 3:00 pm Sun Mar 10, Sat Mar 16, Sun Mar 17 mat, final show.

*** Read Gary Smith’s review in The Hamilton Spectator, March 13, 2019:

Langston Hughes vs. Joe McCarthy is a moving and probing drama

“Langston Hughes vs. Joe McCarthy,” playwright Ron Weihs’s probing drama, packs a lot of power into an hour. This short play, interspersed with elegant stage moves, as well as haunting poetry by the iconic Hughes, is a fusion of art forms that sits neatly on the Artword Artbar stage. The room is small. So is the stage. But the ideas are large.

It’s 1953 and we’re immersed in the aggressive rhetoric of a select American committee that hounded intellectuals and artists. The fiefdom of Joe McCarthy and a band of loutish interrogators, these folks ultimately became the genesis of playwright Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” with its comparison of witch hunts in Salem and the persecutions by the infamous McCarthy Committee in the ’50s.

Weihs’s play, based on Congressional records, presents some of the actual language used as McCarthy struggled to nail the elegant black poet Langston Hughes, suggesting his poems had a communist beat.

Witch hunters were behind every wall and tree in those days, seeking out communist sympathizers unfaithful to the U.S.A.’s increasingly tattered red, white and blue mantra that suggested liberty for all.

Weihs’s play goes beyond the documentation of Hughes’ interrogation, however. It suggests the times, depicted clearly and powerfully in the images of pain that set designer Judith Sandiford projects onto a stark white screen. We see hunger, joblessness, fear and desolation. And we see the segregation and denigration of black citizens, particularly in romantic old Dixie, where they were forced to sit at the back of buses, refrain from drinking from whites-only water fountains and barred from most hotels, dining rooms and movie theatres.

These images, along with the always elegant language of Hughes’s poetry, summon a vision of a world of haves and have-nots. That such a world could be defined simply by the colour of someone’s skin remains as ugly and reprehensible today as it was in the times of Hughes’s powerful poetry.

Fearing the face of communism was about to undermine American values, McCarthy frequently picked on artists and the intelligentsia.

As an important leader in the “Harlem Renaissance,” a movement that celebrated the writers, musicians and intellectual black artists who would shape the diversity of American culture, Hughes was a target. Playwrights such as James Baldwin, musicians such as Duke Ellington, and singers Billie Holiday and Mabel Mercer were faces of this movement, too. The times were changing. Lovely Lena Horne would no longer have her image cut out of prints of Hollywood musicals playing in the Deep South because she was black. Sammy Davis Jr. would soon become a huge star in films, television and Las Vegas.

In a sense this is the background for Weihs’s moving play. It is the kaleidoscope of change that was about to sweep across America. It’s not just about Langston Hughes and Joe McCarthy. It’s about so much more.

Weihs has wisely refused to make his play a virtual confrontation. He has interpolated movement from actor-dancer Learie McNicolls that suggests such yearning, such illuminating thought that Hughes’s poems sing physically as well as aurally.

You long for McNicolls to go on dancing to the throbbing sounds of “Lady Be Good,” “Sunny Side of the Street” and “I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good.”

The play moves gracefully from the probing questions of McCarthy, a gnarled presence with a rumbling rasp of a voice intoned by Howard Jerome, an actor of infinite colours. He makes McCarthy a hard man who finds dark and sinister meaning behind every sweetly constructed phrase of poetry.

McNicolls is a handsome presence with a voice as warm as honey. He makes the confrontations between art and intellect in Weihs’s self-directed play quiver with truth.

Quibbles? Hardly any. The transitions from poetry to dance might be more seamless, and the broad space between the actors to allow for visual projections could be tightened now and then.

Mostly, the play reminds me of the glory days of New York’s Greenwich Village, where poems were read to live jazz and the elegant dance steps of folks like Willy Blok Hansonat the Café Wha? created entertainment that was glorious, yet bizarre.

This one’s for people who like their theatre to be different.

Gary Smith has written on theatre and dance for The Hamilton Spectator for more than 37 years. gsmith1@cogeco.ca